The Triangular Prism of Writing Success

Where science meets self doubt.

There are many different reasons why people write: to achieve recognition, to scrawl "I woz ere" or the wall of the world, to feel the joy of creating good art, or the insane goal of trying to make money. However, assuming you are not at the stage where you can judge your work on reviews, sales, and/or truly independent feedback, how do you tell if you are any good?

"The Cat in the Hat was rejected 99 times, you know."

Yes, thanks, but so was Dr Bonkers' crayon-based "My guide to why scientists are in league with goats to take over the world's cheese and what you can do about it".

So, here is a line. This is what I want to know my position along:

Now, there not being a patended "Qualitomatic 9000" machine which tells you how good writing is, how does one find out?

In the words of shampoo adverts, now the science part.

A lot of science involves indirectly measuring something, by means of measuring something else. They're sometimes called indicator variables.

So, for example, you can't actually spot atoms decaying in a radioactive material, but you can spot the aftereffects of various types of radiation creating an electrical charge in a Geiger counter. You're actually measuring electrical discharges, and to be certain you're doing the right thing you have to eliminate any other reason that charge can be there, such as someone next to you vigorously rubbing a balloon on their trousers. A common scientific problem. Possibly because I like to stand next to scientists while I vigorously rub balloons on my trousers. Don't judge me.

Returning to writing, it's easy to spot the indicator variable. Sadly it isn't people telling you they like your stuff, since they don't, despite our pleas in the writing group I go to for people to "tell me absolutely honestly and bluntly how good you think my writing is." No, an independent person needs to judge it, and in general judge it from a larger-than-one field. And this means, in my case, short story competitions and magazines.

Now, returning to indicator variables, we get to another area of indirect measurement. Because things are somewhat random, you have to realise what you're actually measuring. If I take a standard six-sided die and roll 154436266221, I'd look at that and say, yeah looks vaguely reasonable. But I don't know it's fair - I haven't got nearly enough data for that. If I rolled 112211111212, I might have enough evidence to suspect not all the standard 1-6 sides are as I'd have expected. But with short stories, we get into harder territory. There's a lot of subjectivity. If I wrote one of the actual best short stories ever written and sent it into 10 competitions, I might well still not win any of them. It may be that the level I'm aspiring to would, say, win 1 in 50 medium-to-large competitions. Or even fewer. So we're dealing with what is probably a 200-sided die, and we're rolling it over and over to find out if there are any sides with anything but "abject failure" written on them (I accept this makes it a large die, or very small lettering).

What I'm interested in is whether one of the sides says "shortlisted" and another says "you are a winner!" And without rolling 1000 times this is hard to do.

What one can do, of course, is enter smaller competitions, where perhaps the sides of the die showing quality of your writing are numeric, and you simply have to roll higher than anyone else this time round.

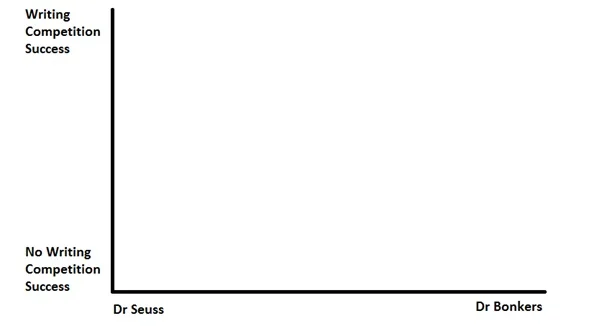

And how does this help our lovely previously-one-dimensional graph?

Well, now it becomes two-dimensional:

And we can put some limits on it now. Because the assumption is, Dr Bonkers won't have as much success as Dr Seuss, so we can draw a triangle (finally we get to the triangle!).

So, as we succeed or fail more in competitions, we can restrict where we are in our writing success triangle.

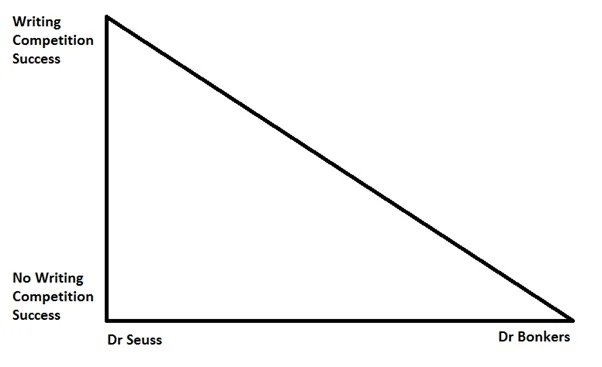

And now we leap forward into the great unknown of some day publishing a book, and how successful said book might be. Accepting that even Dr Bonkers might get lucky, but hoping he won't buck the trend and become too successful, we now draw another axis, this time heading skywards based on popular acclaim for the books wot you write.

And here, finally, we reach our irregular triangular prism of writing success.

So, with every success move up that axis, with every failure move towards Dr Bonkers.

And while we're in danger of trying to make you visualise a cut section of our triangular prism, I feel I've done enough whining for now.

And I think I might also have convinced you, sadly, that I am Dr Bonkers.